SOLAR POWER TO THE PEOPLE

With his work on the viability of solar cells, PhD student Nelson Sommerfeldt is shining a light on the sustainability of this renewable energy source for the Swedish housing market.

Despite Sweden being a country that’s renowned for its unpredictable weather, integrating solar photovoltaic (solar-cell) systems into Swedish cooperative family housing has long been considered a viable and sustainable energy option.

However, the Bostadsrättsföreningar, the councils which manage this type of housing, have to make decisions on which energy providers or power systems will be of greatest benefit to their members. And they need the right information, because a significant amount of each housing council’s budget is spent on their energy supply. They can’t afford to get it wrong.

Yet, little independent information has been available about how, when or where to install solar-cell power technology. That is, until American PhD student Nelson Sommerfeldt stepped in.

By the time Sommerfeldt arrived at KTH from Michigan, funding had already been put aside for a project to investigate solar-cell systems. But with the lack of guidance for potential users it quickly became clear that the project needed to focus on empowering the decision-makers with the facts they needed to allocate their energy budgets. Sommerfeldt takes up the story:

“Three of us have been working on the project: me in Energy Technology and two researchers from the School of Architecture and the Built Environment (ABE), one of whom looks at Real Estate Economics and Management, while the other looks at Building Technology.

“Initially I was solely focused on technique and the application of the solar technology, but that soon changed, as I’m a bit of an economics geek, so I also grabbed onto the economics of the project. We began to try and discover exactly why the councils choose the systems they did.”

Having the correct information on initial, running and projected costs is a key concern. When Sommerfeldt began his research he soon became aware that most of the information concerning the economic viability of solar power was in the hands of energy companies. He could see that there were few independent bodies providing substantial data on the cost efficiency of solar power.

“We did four or five case studies and I looked into the tech and economics,” he explains. “It was a three-year project which finished last spring. Part of the project was to produce a handbook as a first point of information for the housing councils to get practical information about solar power.”

Although only a short report was required, Sommerfeldt believed that something a little more in-depth was necessary and so the team produced a longer report in English to reflect their work.

“The project was supposed to be finished in December 2015 but we decided to wait and present it in the spring of 2016. We did that on a beautiful sunny day in April–excellent conditions for discussing solar energy,” he says, smiling.

Sommerfeldt and team were overwhelmed by the response.

“We published the report online at the same time as the print copy was released and we held a seminar here at KTH. There were more people at the seminar than we could actually fit in the room. We had people travelling from all over the place to attend. There were a lot of energy managers from municipalities there, but the head of research from Vattenfall, CEOs of tech start-ups, and a number of politicians also attended, so we were very happy.”

Between the online and print versions, over 1000 copies of the report have been distributed, giving people more access to information that can enable them to make informed decisions on choosing their energy supply. Now, with the costs of solar-cell technology decreasing, these sustainable and renewable energy systems are becoming more accessible.

And considering Sweden’s goal of relying 100% on sustainable energy by 2040, perhaps the team’s report has come at just the right time.

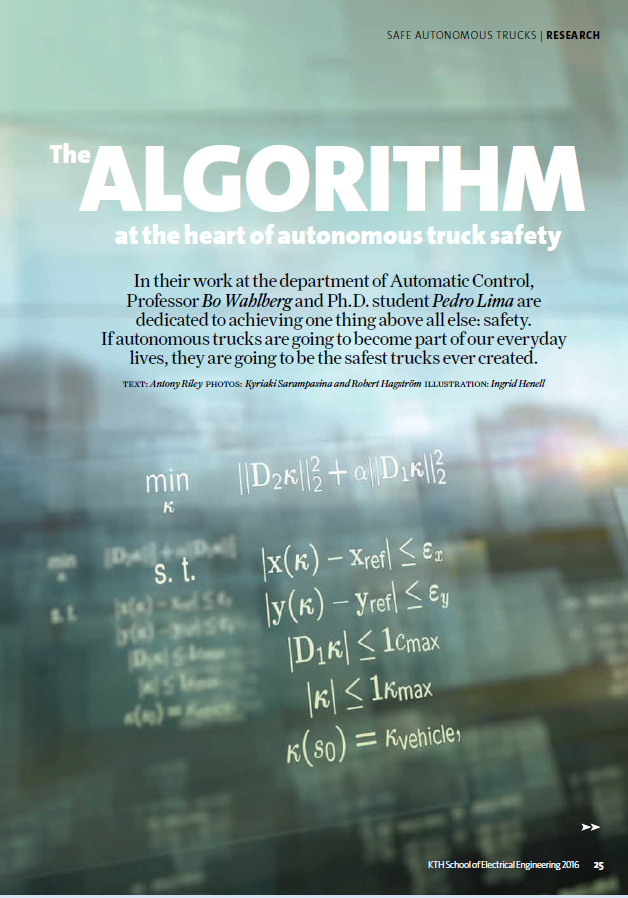

THE ALGORITHM AT THE HEART OF AUTONOMOUS TRUCK SAFETY

The algorithm at the heart of autonomous truck safety

In their work at the department of Automatic Control, Professor Bo Wahlberg and Ph.D. student Pedro Lima are dedicated to achieving one thing above all else: safety.

If autonomous trucks are going to become part of our everyday lives, they are going to be the safest trucks ever created.

Many accidents we see on the roads today are caused by what is known as 'pilot-induced oscillation', which Professor Wahlberg says “is ultimately due to the fear induced in the driver in a dangerous situation, causing them to overact or overcompensate”.

But a well-designed algorithm doesn’t react like that; it computes what needs to be done and reacts accordingly, causing an autonomous or self-driving vehicle to continue safely on its way. And it’s this that Wahlberg and his team at the Department of Automatic Control are focused on creating. However, working towards such an algorithm hasn’t been easy, and Wahlberg says that it would have been impossible to develop even five years ago.

“We just didn’t have the computational power. The ideas are not completely new, but the ability was not there.”

Doctoral student Pedro Lima agrees: “What we are using is Model Predictive Control (MPC), and that is not a new concept. It actually existed as early as the 1960s, but running a complicated optimisation algorithm this fast wouldn’t have been possible before, without today’s computers.”

Lima is a fervent advocate of automated driving technology. He explains his motivation with a stark statistic.

“This week I attended a conference where I learned that 1.2 million people die every year due to road accidents. That’s like a jumbo jet falling from the sky every half a day,” he says, still genuinely shocked by what he has heard. Despite this disturbing picture he is far from despairing because of the possibilities offered by the project he is working on. “In the future people will look back and say ‘how on earth did people actually drive a car?’ It’s so dangerous,” he says.

Automatic Control and safe transport

The Department of Automatic Control at KTH is a busy place, befitting the fact that automation is one of the hottest research subjects going, and also a much-anticipated technology by consumers and industry alike. Along with his colleague Assistant Professor Jonas Mårtensson, Professor Wahlberg supervises Lima’s research, which focuses specifically on control algorithms of heavy-duty construction trucks, and he has spent the past four years working on Model Predictive Control (MPC). “Using MPC a truck can stay on a narrow, winding road and drive itself smoothly,” Wahlberg says.

Lima adds, “The model can predict the vehicle's movements in any given situation, on the basis of information about what direction it's being steered in, how much throttle is given and alternatively how much braking force is applied.”

In the work, a lot of effort has been expended on developing the truck’s control algorithm so that it is as accurate and reliable as possible, but achieving this with a heavy truck is no mean feat. With much greater mass and much more built-in inertia than passenger cars, trucks present a greater challenge for autonomous driving technology.

When it comes to automated vehicles in general, the question of safety is at the forefront of everyone’s mind, but there is a significant cultural mindset to overcome: many of us are scared to let go of the steering wheel.

However, Wahlberg says that this is all a matter of public perception. Lima’s work notes that figures for 2012 from the USA’s national highway safety administration (NHTSA) showed that 94% of accidents are caused by driver error. Indeed, the World Health Organisation (WHO) predicts that road traffic injuries will be the third greatest cause of disabilities by 2020. Yet, despite those statistics the public are still wary of autonomous vehicles, preferring to have humans in control.

How automated trucks can make mines safer

The project ‘iQMatic’, led by KTH partner Scania AB, has the objective of developing a fully autonomous truck for mining operations by 2018. Pedro Lima spends roughly twenty percent of his time working with Scania at its research and development department in Södertälje, where he is developing the ‘essential controller’.

“The essential controller is a way to automatically control the steering, gas and brakes,” Lima explains. He adds that he likes to focus on the steering most of all, and the Model Predictive Control technology makes it possible to minimise deviations from the driverless vehicle’s intended path. The MPC also maximises passenger comfort by reducing involuntary side-to-side movement in the steering, acceleration and braking, while finally maximising the vehicle's fuel efficiency. The team is focused on ensuring that the automated vehicle drives as smoothly and as safely as possible.

Tests so far have impressed professional drivers. The prototype, ‘Astator’, travelled softly and stably around a track at Scania’s testing area in Södertälje, achieving its maximum speed of 90 km/h. The algorithm smoothes the drive by taking in new information every 50 milliseconds, causing it to make the vehicle steer, accelerate and brake correctly.

The Global Positioning System (GPS), LIDAR (Light Detection and Ranging, a remote sensing technology that uses light in the form of a pulsed laser to measure ranges) and multiple cameras all make an autonomous truck much more aware of its situation and position than a conventional unautomated truck with an unassisted driver. This awareness, allied to an ability to automatically assess and correct direction, speed and braking ensures that the trucks of the future will be very much safer alternatives to the vehicles currently in use.

By 2018 we are highly likely to see autonomous trucks working in mining environments in what will be highly controlled situations. When automated vehicles are used in mines, it is most likely that people will be placed in separate control towers overseeing the larger picture and giving the vehicle its tasks; that means the risk to people working at an often busy mine would be greatly reduced. This will be a great step forward in increasing the safety of mineworkers.

Though automated vehicle technology is still developing, Bo Wahlberg is already certain about the improvements in safety that it will bring.

“Although we cannot be sure of what the future holds beyond the mines and more controlled environments, we are sure that Model Predictive Control has the ability to bring not only advances in general vehicle autonomy but also in road safety overall.”

EDITOR - PRESIDENT KTH ROYAL INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY BLOG

Editor of the Presidents weekly blog in English

I edit the English version of the weekly blog.

EDUCATION: ENGINEERING THE PERFECT BALANCE

Engineers have been trained at KTH Royal Institute of Technology for over 100 years. Teaching practice has always evolved and adapted both with the college and society at large. Today, striking a balance between theory and practical experience is at the centre of the most recent education reforms.

The balance ensures that the university delivers professionals with relevant practical experience, in addition to being schooled in the fundamental scientific rigour that must underpin that practice. However, a balance between science and practice has not always been to the aim of the university.

Post-world war one KTH was a very different institution to today’s university. If you were to visit you would have found a male-dominated training college, much more of a ‘workshop’ with an apprenticeship style. Similar to today’s facility it was a proud institution in which students could expect the best training in the latest methods when studying in fields such as materials science. But it was certainly, without question, more traditionally focused. Training was rooted in the apprenticeship system for tradesmen. Water engineers could for instance make use of the special V-shaped building (known as the trouser legs) where the basement of one ‛leg’ had large water channels that could be used for various experiments. It was very much a ‘hands-on’ school.

However, after time it had become clear that the school was going to need to move towards more theory. And so in 1867 “scientific training” was entered into the university’s statutes. Theory began to occupy more space in the curriculum.

A leap forward and we find ourselves in the 1990s, and now the tables have very much turned. By this time there were very few internships being offered by industry and the practical requirement for a degree was removed altogether. At KTH many professors themselves had little or no practical experience and theoretical work and research became all dominant.

“In engineering education in the 1990s there was nothing about conceiving, there was nothing about implementing or operating, it was all design or calculations.” Says Joakim Lilliesköld, Associate Professor in Industrial Systems Engineering, and the man responsible for education at the School of Electrical Engineering. Critics were also looking to engineering colleges around the world and feeling that the focus on the profession was being left behind. In the US, Boeing the multinational corporation and engineering giant, had made the observation that they were unhappy with the graduates that they were getting. As Lilliesköld describes it “they, as well as many other companies, were not really happy with the engineers that came out of the system, they wanted to see a change in their education so that they would get more practice into it and they took a systems approach to how to re-train them.” It was out of this that the ‘CDIO’ method was born in the early 2000s. The method focuses on

four key areas that the students need to work with in order to become rounded engineers; Conception, Design, Implementation, and Operation.

“CDIO was a project funded by Wallenberg where they provided money to three Swedish university’s; Chalmers, Linkoping and KTH, and M.I.T in the US – the goal was to educate engineers that can engineer,” says Lilliesköld.

CDIO said that engineering programmes needed to have all four fundamental puzzle pieces. Additionally, it was realised that for the ‘hands-on’ aspect, project courses would also need to be added to the curriculum. Lilliesköld explains how the model was added to and adjusted, “another dimension was realised – that you had to have a progression of skills. So a long set of engineering skills was developed, you needed to be able to work in a team, to do a project plan, to be able to communicate. All of the skills of the engineer were examined.” A key feature of CDIO was the way in which it was ‘baked in’, the skills were not taught separately — there was not a project management course or a technical writing course — they were integrated into the actual technical courses. CDIO has continued to develop and the curriculum at KTH’s School of Electrical Engineering has adapted and evolved.

At KTH this most recent evolution of education started in 1999 when the first year project course began. According to Lilliesköld it created a lot of discussions as to whether or not you could present an application before all relevant theories were known. Another issue was the product focus of CDIO, in early 2000 it was difficult for many at the department to talk about products for Electrical Engineering. Then something changed. Project courses were developed in many of the master programs. In 2007, the bachelor thesis was added to the curricula as a result of the Bologna reform. 10 years later, the next step was taken to introduce a more challenging project course in the 2nd year at the bachelor level. Then, in 2013 the curriculum was rebuilt. The result was a program to create world-class electrical engineers. A course with both a strong theoretical base and one project each year to tie the theoretical courses together. Additionally, there is a course called Global Impact of Electrical Engineering that looks at future challenges and introduces students to a mentor from the faculty. As Lilliesköld says, “Altogether, students now leave with a good mix of skills, ready for the demands of 21st-century industry.