THE ALGORITHM AT THE HEART OF AUTONOMOUS TRUCK SAFETY

The algorithm at the heart of autonomous truck safety

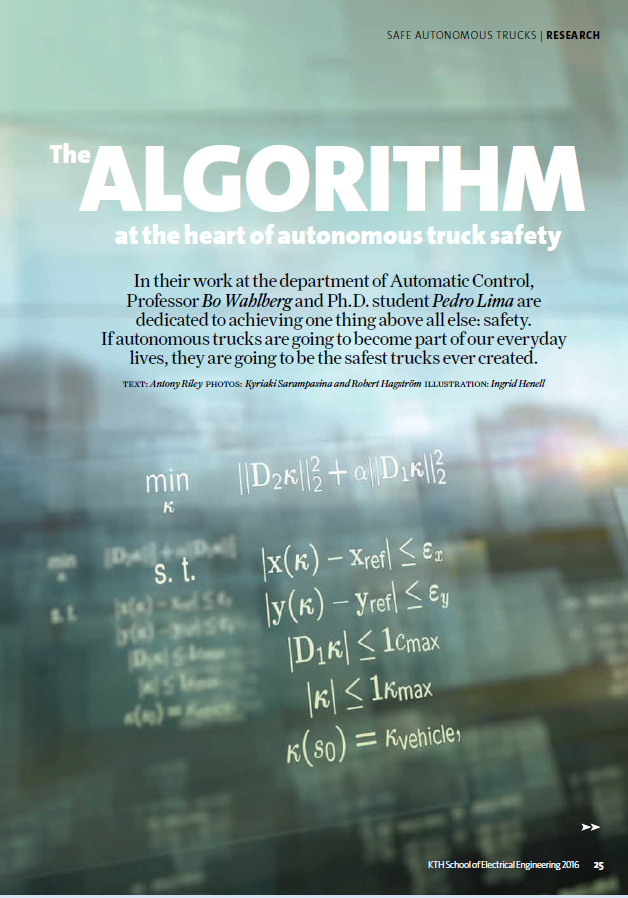

In their work at the department of Automatic Control, Professor Bo Wahlberg and Ph.D. student Pedro Lima are dedicated to achieving one thing above all else: safety.

If autonomous trucks are going to become part of our everyday lives, they are going to be the safest trucks ever created.

Many accidents we see on the roads today are caused by what is known as 'pilot-induced oscillation', which Professor Wahlberg says “is ultimately due to the fear induced in the driver in a dangerous situation, causing them to overact or overcompensate”.

But a well-designed algorithm doesn’t react like that; it computes what needs to be done and reacts accordingly, causing an autonomous or self-driving vehicle to continue safely on its way. And it’s this that Wahlberg and his team at the Department of Automatic Control are focused on creating. However, working towards such an algorithm hasn’t been easy, and Wahlberg says that it would have been impossible to develop even five years ago.

“We just didn’t have the computational power. The ideas are not completely new, but the ability was not there.”

Doctoral student Pedro Lima agrees: “What we are using is Model Predictive Control (MPC), and that is not a new concept. It actually existed as early as the 1960s, but running a complicated optimisation algorithm this fast wouldn’t have been possible before, without today’s computers.”

Lima is a fervent advocate of automated driving technology. He explains his motivation with a stark statistic.

“This week I attended a conference where I learned that 1.2 million people die every year due to road accidents. That’s like a jumbo jet falling from the sky every half a day,” he says, still genuinely shocked by what he has heard. Despite this disturbing picture he is far from despairing because of the possibilities offered by the project he is working on. “In the future people will look back and say ‘how on earth did people actually drive a car?’ It’s so dangerous,” he says.

Automatic Control and safe transport

The Department of Automatic Control at KTH is a busy place, befitting the fact that automation is one of the hottest research subjects going, and also a much-anticipated technology by consumers and industry alike. Along with his colleague Assistant Professor Jonas Mårtensson, Professor Wahlberg supervises Lima’s research, which focuses specifically on control algorithms of heavy-duty construction trucks, and he has spent the past four years working on Model Predictive Control (MPC). “Using MPC a truck can stay on a narrow, winding road and drive itself smoothly,” Wahlberg says.

Lima adds, “The model can predict the vehicle's movements in any given situation, on the basis of information about what direction it's being steered in, how much throttle is given and alternatively how much braking force is applied.”

In the work, a lot of effort has been expended on developing the truck’s control algorithm so that it is as accurate and reliable as possible, but achieving this with a heavy truck is no mean feat. With much greater mass and much more built-in inertia than passenger cars, trucks present a greater challenge for autonomous driving technology.

When it comes to automated vehicles in general, the question of safety is at the forefront of everyone’s mind, but there is a significant cultural mindset to overcome: many of us are scared to let go of the steering wheel.

However, Wahlberg says that this is all a matter of public perception. Lima’s work notes that figures for 2012 from the USA’s national highway safety administration (NHTSA) showed that 94% of accidents are caused by driver error. Indeed, the World Health Organisation (WHO) predicts that road traffic injuries will be the third greatest cause of disabilities by 2020. Yet, despite those statistics the public are still wary of autonomous vehicles, preferring to have humans in control.

How automated trucks can make mines safer

The project ‘iQMatic’, led by KTH partner Scania AB, has the objective of developing a fully autonomous truck for mining operations by 2018. Pedro Lima spends roughly twenty percent of his time working with Scania at its research and development department in Södertälje, where he is developing the ‘essential controller’.

“The essential controller is a way to automatically control the steering, gas and brakes,” Lima explains. He adds that he likes to focus on the steering most of all, and the Model Predictive Control technology makes it possible to minimise deviations from the driverless vehicle’s intended path. The MPC also maximises passenger comfort by reducing involuntary side-to-side movement in the steering, acceleration and braking, while finally maximising the vehicle's fuel efficiency. The team is focused on ensuring that the automated vehicle drives as smoothly and as safely as possible.

Tests so far have impressed professional drivers. The prototype, ‘Astator’, travelled softly and stably around a track at Scania’s testing area in Södertälje, achieving its maximum speed of 90 km/h. The algorithm smoothes the drive by taking in new information every 50 milliseconds, causing it to make the vehicle steer, accelerate and brake correctly.

The Global Positioning System (GPS), LIDAR (Light Detection and Ranging, a remote sensing technology that uses light in the form of a pulsed laser to measure ranges) and multiple cameras all make an autonomous truck much more aware of its situation and position than a conventional unautomated truck with an unassisted driver. This awareness, allied to an ability to automatically assess and correct direction, speed and braking ensures that the trucks of the future will be very much safer alternatives to the vehicles currently in use.

By 2018 we are highly likely to see autonomous trucks working in mining environments in what will be highly controlled situations. When automated vehicles are used in mines, it is most likely that people will be placed in separate control towers overseeing the larger picture and giving the vehicle its tasks; that means the risk to people working at an often busy mine would be greatly reduced. This will be a great step forward in increasing the safety of mineworkers.

Though automated vehicle technology is still developing, Bo Wahlberg is already certain about the improvements in safety that it will bring.

“Although we cannot be sure of what the future holds beyond the mines and more controlled environments, we are sure that Model Predictive Control has the ability to bring not only advances in general vehicle autonomy but also in road safety overall.”

A FRICTION FIGHTER WITH A DREAM

Growing up with two volcanologist parents on the seismically active eastern edge of Siberia, Sergei Glavatskih seemed destined to be a scientist too. Now he uses chemistry and physics to take lubrication to the next level.

The son of two volcanologists, Sergei Glavatskih had a pathway into research that was in some ways preordained. “I was, by default, set for science,” Glavatskih reflects from his nondescript office at the Royal Institute of Technology (KTH) in Stockholm, Sweden. Raised on Russia’s far eastern Kamchatka peninsula, the land of volcanoes, he often “helped” his mother during summer research trips to geothermal fields and the Commander Islands.

Glavatskih says when he was growing up he always had a head full of questions, but at school he found his teachers tired and uninterested. Correspondence courses filled in some of the gaps in his learning, particularly in physics and mathematics, and there was the National Geographic, “one of the few magazines that remained relatively censor-free”, he says. In its pages he learned about people and places beyond his beautiful but cut-off homeland.

We should pursue impossible dreams sometimes, and if we are successful there will be incredible gains for society.

SERGEI GLAVATSKIH

Forgoing military service (and quite possibly, he believes, the war in Afghanistan) by attending university in Moscow, Glavatskih earned a master’s in mechanical engineering and went on to his first PhD, in cryogenics. He developed patented resonance sensors, later used in the refuelling system of a passenger aircraft, the TU-154, which operated on liquefied natural gas.

When the Cold War came to an end, Glavatskih left Russia, both to satisfy his yearning to travel and to begin his international research experience. “It was easier to come to Scandinavia, and I always liked the idea of Sweden,” he says. In Sweden Glavatskih embarked on his second PhD, in machine elements, which led to his work with Statoil on the development of environmentally adapted synthetic oils. The oils TURBWAY SE and TURBWAY SE LV became commercially available for rotating machinery.

Friction, as an area of research, has held increasing fascination for Glavatskih. He explains that it is one of the most fundamental areas in engineering and has been a concern of humankind since the earliest of times. Now it is more important than ever because of the amount of energy that the world produces and consumes, the associated losses and the consequent environmental implications.

Glavatskih says that many of today’s problems with machine efficacy come down to inappropriate lubricants and “just incremental” lubricant development over the years. Typically, he explains, machines are designed, and then it is decided which of the available lubricants to use based on viscosity.

“In many cases,” he says, “lubricants are regarded as chemical additives to an engineering solution.” Lubricant development is carried out by chemists and, as such, is considered almost a black art by mechanical engineers.

Sergei Glavatskih

“We need to incorporate more advanced lubricant technologies in machine design and even new properties previously not possible with traditional lubricants to ensure the necessary improvements,” he says. “This can be achieved through a mechano-chemical approach, so we should use our knowledge of chemistry on a molecular level and some physics and mechanics to give lubricants new properties to enable new technologies.

“If you look back at history, even in the 19th century, the great scientists did not define themselves as scientists in ‘machine elements’ or ‘thermo-dynamics’,” Glavatskih explains. “They did many things in many different subjects. Unfortunately, for some reason, as time went on, everything became more ‘siloed’ – it has all become so narrow. As a result of that we have to change things about the way we work.”

The way in which researchers and scientists work stems naturally from the way they’ve been educated. As a scientist Glavatskih feels strongly that the educational aspect of his work at KTH is just as important as the research he is engaged in. “We must further investigate and consider the way we are teaching and training the engineers of tomorrow,” he says, adding that his work will plant the seed for a non-linear, collaborative and innovative way of thinking and working.

At KTH, Glavatskih leads a diverse team of researchers from backgrounds such as nano-technology, chemistry and fluid mechanics. “Our starting point is that we consider a lubricant a machine element in itself,” he says. The notion of lubricant as an integral part of the machine is key to Glavatskih’s design philosophy.

One of Glavatskih’s current research projects, supported by the Swedish Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation, is an investigation into ionic liquids (room temperature molten salts). Glavatskih and his team are exploring the potential of these ionic compounds in lubrication. Their results show that ionic liquids can serve as a key technology enabler in lubrication. A multiscale approach to the lubricant design developed by the team enables tuning the temperature, pressure and shear response of the ionic liquids to provide lubricants with desired properties. Important aspects of the design procedure are sustainable synthesis paths and a lower environmental impact.

It is possible, in situ, to control friction performance of the tailored ionic liquids, which is unachievable with conventional molecular lubricants. His vision is to bring to the market the novel “active” approach to the problem of friction and wear reduction in lubricated contacts, manipulating in real time the rheology and near-surface structure of the lubricants based on the tailored ionic liquids.

“My job as a scientist is to be a little crazy,” says Glavatskih. “We should pursue impossible dreams sometimes, and if we are successful there will be incredible gains for society.”

Sergei Glavatskih

Born: 1966.

Lives: Stockholm, Sweden.

Works: Royal Institute of Technology (KTH), Stockholm, Sweden, and Ghent University, Ghent, Belgium.

Education: Master’s in mechanical engineering, honours diploma, 1989, Bauman Moscow State Technical University; PhD in cryogenics, 1994, Bauman Moscow State Technical University; PhD in machine elements, 2000, Lulea University of Technology (LUT); docent in machine elements, 2003, LUT.

Currently reading: Vikingarnas Värld(Viking World), by Kim Hjardar.

EDITOR - PRESIDENT KTH ROYAL INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY BLOG

Editor of the Presidents weekly blog in English

I edit the English version of the weekly blog.

LUXE ON DEMAND

An article for Inspire manazine by Iggeusund Paperboard. The article focuses on the concept of luxuary as opposed to quality...